Whether it’s Libyan reggae or Lebanese funk, Habibi Funk are reissuing unknown records that deserve to be heard.

“It’s just normal for me to be in front of my computer until 3 a.m., clicking through photos to try and find someone,” Jannis Stürtz says before adding, “Anyone who is not part of this world would probably feel like I’m a crazy stalker.”

The world in question is Habibi Funk Records, a Berlin-based label that re-releases eclectic music from across the Middle East and North Africa.

Habibi Funk records have a visibly shared identity and a devoted following, but defining the music that the label covers is a tough ask. It would be easy to say it’s Arabic-language music from the 1970s and ‘80s, but they’ve also released an Amazigh-language album from Algerian artist Majid Soula, Chant Amazigh. Or you could say it’s Middle Eastern funk and disco, but then again, they’ve also released music by Ibrahim Hesnawi, the father of Libyan Reggae.

When Stürtz, co-founder of Habibi Funk and DJ under the same name, explains the label’s focus, he sidesteps any attempt to define it by genre. “It’s wherever artists were taking influences from outside their local context and trying to adapt it, finding a way to translate it and make it their own,” he says.

Many of their records draw on genres with origins in the U.S., such as soul and funk. Other times, the label works with artists who pull influences from Congolese or Ethiopian music.

Stürtz first developed an interest in Arabic music while digging in Morocco. In the years since, the label has sought out music that they are both excited by and is relatively unknown. That often means working with records that aren’t digitally available.

Habibi Funk records have a visibly shared identity and a devoted following, but defining the music that the label covers is a tough ask. It would be easy to say it’s Arabic-language music from the 1970s and ‘80s, but they’ve also released an Amazigh-language album from Algerian artist Majid Soula, Chant Amazigh. Or you could say it’s Middle Eastern funk and disco, but then again, they’ve also released music by Ibrahim Hesnawi, the father of Libyan Reggae.

When Stürtz, co-founder of Habibi Funk and DJ under the same name, explains the label’s focus, he sidesteps any attempt to define it by genre. “It’s wherever artists were taking influences from outside their local context and trying to adapt it, finding a way to translate it and make it their own,” he says.

Many of their records draw on genres with origins in the U.S., such as soul and funk. Other times, the label works with artists who pull influences from Congolese or Ethiopian music.

Stürtz first developed an interest in Arabic music while digging in Morocco. In the years since, the label has sought out music that they are both excited by and is relatively unknown. That often means working with records that aren’t digitally available.

Travel through medinas throughout the Middle East, and you’ll often come across tiny, tucked-away shops full of bric-a-brac, old family photos, broken landlines, and, frequently, vast stacks of tapes and vinyl. An entire wealth of music history that isn’t widely known.

“We’re trying to find a new audience for music we think is great, and we try to be the bridge between the artist and people who might enjoy it as much as we do,” Stürtz elaborates. They’ve built a solid track record of doing exactly that.

Part of the label’s success is due to its selection reputation. Their releases are often eagerly anticipated by a dedicated audience who know that, in all likelihood, they’ll be unfamiliar with the artist but implicitly trust the label’s taste.

For Habibi Funk, building that reputation and marketing the material is a significant part of re-releasing. The label recoils from building hype around claiming to have “found” these “lost” records. The music they work with isn’t lost. It’s just not widely known. Making it known is their concern. Pure and simple.

While that often means digging in its most traditional sense and actively seeking out music on the ground, as the label has grown, it’s also been able to tap into and build networks of people looking out for them and bringing records to their attention.

One such encounter occurred when Stürtz joined Lebanese artist Issam Hajali for coffee a few years back. Mid-conversation, the musician, whose beautiful folk music the label re-released in 2019, suddenly disappeared and then re-emerged from his basement with a record.

Although the records are a testament to the exchange and interchange of musical ideas and identities across borders, few garnered international attention in their time. In releasing this wide variety, Habibi Funk introduces new listeners to music they might never have heard otherwise.

Now, as Habibi Funk is growing, those encounters are becoming more common, “but sometimes there definitely is still a classic digging aspect; I buy a bag of tapes, listen through them – finding a random tape in a shop is definitely still something that happens,” Stürtz clarifies, recounting a recent trip to a cassette shop while playing in Dubai.

They view themselves as part of that network, often extolling the vibrant vinyl and cassette culture that exists across the Middle East and North Africa and frequently sharing the places they encounter music on their social media.

“I don’t like the whole gatekeeping, keeping shit secret approach that is sometimes affiliated with digging,” Stürtz affirms. “In the end, these shop owners and dealers are part of the ecosystem that allows us as a label to function and work.”

That ecosystem helps them find music and can also help alleviate the challenge of finding the artist. An arduous, research-intensive element of the label’s work is trying to find the artist and uncover their story. Then, the label can work with them and bring their music to an audience.

“It’s important for us that ownership remains with the artist,” explains Stürtz. “We are just a partner they work with [to] make their music available.” Rather than buy the rights, the label licenses them and splits profits equally with the artists.

In many cases, their vast network can help the label find an artist within hours, but in other instances, scrolling through niche Facebook groups for contacts can have the team up until the early hours. It’s taken years to track down an artist or their family before.

“Availability” is a theme that Stürtz returns to regularly – digitization is a key part of that, given the shift in music consumption and the risk of destruction facing physical records. A track being digitally available doesn’t automatically mean that people will listen, especially with how vast the ocean of available music is today.

“‘Ayonha’ was the closest we’ve ever gotten to having a hit,” says Stürtz, “I think the song has been on DSPs (digital service providers) for eight years and had gathered 8,000 streams when we started working with it.”

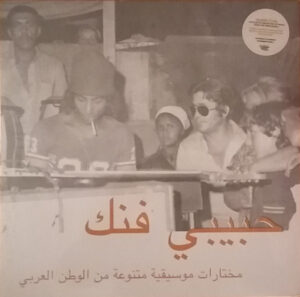

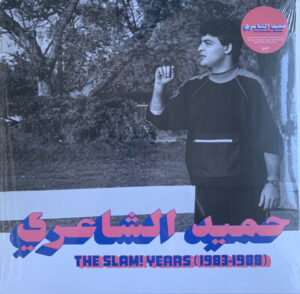

The label included the catchy dance track on a compilation in 2017, Habibi Funk (An Eclectic Selection Of Music From The Arab World), as well as an album entirely dedicated to Hamid El Shaeri’s music in 2022, The Slam! Years (1983-1988).

“And now,” continues Stürtz, “I think it’s at 16 million.”

That jump is a testament to the reach and pull of Habibi Funk Records. After all, it’s about increasing awareness and ability of the music – not putting it aside or holding it up as some relic. “We are not a museum, we are not a cultural institution, we are a record label.”

Source – Discogs